Bug Thy Neighbor

TIME, March 6, 1964

Science/Electronics

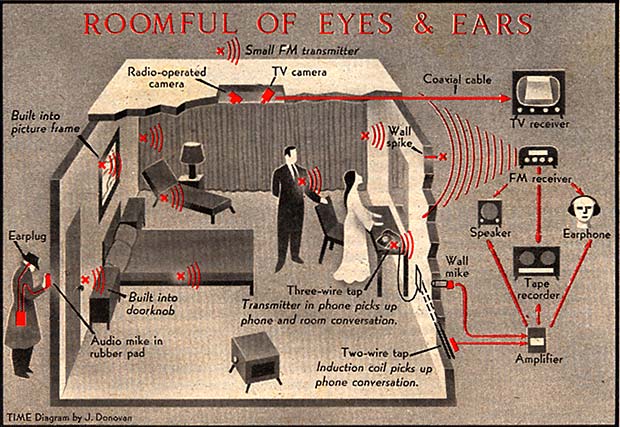

Eavesdropping may not be nice, but it gets niftier all the time. From gleaming electronics factories and grubby back-street workshops has come an ever-subtler array of "surveillance instruments" to penetrate the individual's privacy. The devices are now so easy to plant and so hard to detect that their likely victims-lovers or diplomats, criminals or key executives-can seldom be wholly sure any more that confidential conversations are not being overheard or recorded. Private eyes have become private ears, and they have never been more prosperous. They wire executive suites, washrooms, bedrooms. They tail cars, listening from a safe distance to every word spoken inside them.

Many police forces have elaborate electronic departments. Clandestine eavesdropping has featured increasingly in big-time legal battles, including the Bobby Baker hearings in Washington and Frank Sinatra Jr.'s kidnapping case. Not too unhappily, Andrew J. Palermo, chief investigator for Boston's Central Secret Service Bureau, allows: "Nobody is safe anywhere."

Scientific snooping is not new, but it has been virtually transformed in the past decade by the transistor and its relatives, which can be made almost invisibly minute. A practical radio transmitter with battery and microphone today may be as small as a lump of sugar and yet powerful enough to send a message several hundred feet.

Anything for Anyone. Thanks to the cold war, corporate rivalries and Big Crime-not to mention old-fashioned marital jealousy-curiosity has built a fat-cat industry. The Federal Government alone is believed to buy about $20 million worth of bugging gear a year. Moreover, this total does not include all purchases by the bug-infested CIA, which likes to shop through dummy agencies. No manufacturer admits selling to hoods or pleasure snoopers, but most of them believe that their competitors do. Says Fred East, Los Angeles County district attorney's investigator: "Anyone can buy any kind of bugging device if he's got the money."

The classic snooping device is the tap, which diverts some of the current flowing in the wire of a telephone. No direct connection with the wires is needed; a small induction coil placed beside them repeats fluctuations of the current, which an amplifier and earphones turn into intelligible sounds. Though highly sophisticated and still widely used, the wiretap has one big practical drawback. It has to have a wire leading to the investigator or his tape recorder, thus risking his detection by a trained countersnooper.

Antennas in Bushes. Bugs, the small easily hidden radio transmitters favored by most supersnoopers, are much safer. Usually they have a battery, a microphone to pick up sound waves, and FM circuitry, and they commonly broadcast on 50-100 megacycles, penetrating walls and other obstructions. Their range may be half a mile or a few feet. The electronic eavesdropper, who may be a blackmailer, a divorce detective or an FBI agent, sets up his ultra-sensitive receiver in a rented room or a car parked close enough so that bugged voices come through loud and clear.

Most bugging is done with simple apparatus, since the tiny transmitters usually have to be abandoned on the job. The smallest bug in common use is about one inch square, and it must be clipped to a metal object or trail a few feet of wire to serve as an antenna. Its range may be a few hundred feet. In such areas as residential Beverly Hills, where rooms are hard to rent and cars cannot be parked on the streets at night, the electronic sleuth buries a brick-size repeater in the victim's yard, threading its antenna wire into a bush. The repeater picks up the weak signal from a bug in the victim's house and re-broadcasts it in sufficient volume to be heard beyond the restricted area.

Security Kit. The private ear can buy a "security kit" for about $300. Mosler Research Products Inc. of Danbury, Conn., which claims half the industry's legitimate sales, packs its sets into handsome, standard-size briefcases.

Typical contents:

- An ultra sensitive battery-operated radio receiver with earphones and connections for tape recorder.

- A small audio amplifier with loudspeaker.

- An induction coil, two inches long and three-quarters of an inch in diameter, that can be set beside the wire to tap a telephone.

- A radio transmitter that slips easily into the jacket pocket or handbag, transmits nearby voices to a receiver three blocks away.

- A microphone embedded in a bite-size rubber pad (1 � inches square, one-quarter inch thick) that can be carried in the investigator's palm, attached to an amplifier in his coat pocket; when pressed against a phone booth or a door, it relays the action through an earplug that looks like part of a hearing aid. Hotel dicks love it.

Ears in Cigarettes. Mosler Vice President Ralph V. Ward believes that the best all-purpose bug is a "three-wire tap": a small transmitter that can be fitted in less than a minute into the base of a telephone. When clipped to the proper terminals, it picks up every word spoken both ways over the telephone, monitors ordinary conversations in the room when the phone is not in use. It transmits what it hears by radio; powered by the telephone wires, it works indefinitely. A device at the receiving end translates dialing clicks into the telephone numbers that have been dialed.

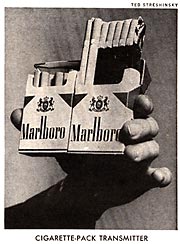

To advance the art, Hal Lipset, a seasoned San Francisco private eye, maintains a laboratory behind a false warehouse front where his eavesdropping "genius," Ralph Bertsche, works out new gimmicks such as a high-powered bug that fits into a pack of filter-tip cigarettes. It is padded to feel soft and shows the ends of real cigarettes to reassure a suspicious businessman or divorce-prone spouse-provided he doesn't ask for a smoke. Bertsche believes that bugs in time may be no bigger than a pencil eraser, recorders as small as a cigarette lighter. *

While miniaturization is now limited to the battery, which must be big enough for adequate power and duration, Bertsche believes that nuclear-energy sources may solve even this difficulty. Already in hand are means to switch off a bug by radio from a distance to save its battery during dull periods. Another battery-sparing device works by sensing the electrical capacity of the human body; it can turn on a bug when people come into a room or climb into a bed.

*However, stories of bugged martini olives in a Moscow bar are apocryphal since 1) the liquid would deflect sound waves, and 2) Moscow bars can be more effectively studded with conventional bugs.

Built Right In. In California, with its high divorce rate (half as many as marriages), high incomes and highly sophisticated industries, is the hard-heartland of the U.S. bugging industry. Espionage is so commonplace in oil, chemical and aerospace companies that many California executives begin to fidget if a visitor so much as sets a briefcase beside him. Another busy Bugsville is Miami, where horseplayers, weekending couples and Latino intrigue support a host of electronic moonlighters who make eavesdropping gadgets in their spare time and sell to anybody.

In fact, official surveillance organizations, such as the FBI, have expertly bugged rooms spotted through leading hotels. When they want to tune in on a guest, they ask the hotel management to steer him to one of these sonic studios. If the guest balks, an agent needs only a few minutes to sneak up and secrete several bugs in the room assigned the visitor; then a team of technicians moves into an adjoining room to set up listening and recording apparatus.

Siphoned Sound. Private detectives-fortunately-cannot count on cooperation from hotel managements, but they can often get into a victim's room by bribing subordinate employees. If the job is important and well paying, they try to plant at least three bugs to catch low-toned conversations in all parts of the room; then tiny cameras, often hidden in radiators or air conditioners, can be triggered by radio control. The most advanced still cameras advance their own film and adjust their shutters to different lighting conditions, but for a really fancy job a TV camera is the thing. Though it takes hard-to-hide coaxial cable, the TV set need be only eight inches long and an inch or so in diameter; its lens can peer through an inconspicuous opening such as a heating duct or recessed light fixture.

If the sleuth cannot get into the target room, he will usually work from an adjacent room or corridor, where he may be able to slip a bug into an electrical outlet or heating duct, which are often back-to-back. Otherwise, he may drill a small hole through the wall and poke a thin plastic tube into it, just short of the far surface, so as to siphon sound waves into a microphone next door.

One last resort for frustrated bug planters is a special mike attached to a sharp spike; driven through the wall, it vibrates with the surface on the far side. But, like esoteric radar beams that pick up the vibrations of distant window glass, spike mikes are apt to be defeated by stray noise unless conditions are perfect.

Smart victims can fight back. One fairly effective weapon is a broad-band radio receiver that gives a squeal if a bug is transmitting nearby. Another anti-bug is carried around the room while the occupant keeps talking loudly; if he hears his own voice in the earphones, he is listening to the output of a hidden bug. The best defense is a thorough, periodic search by an electronic exterminator. Otherwise, anyone who suspects he is being bugged should talk in low tones and keep a radio or TV squawking loudly. One spy fiction dodge, turning on the shower, is useless since the "white sound" of falling water can be electronically filtered out from human voices.

Floating Diplomats. Real-life modern embassy buildings-not only in Russia-have swarms of bugs in their steel-and-concrete bones. Even after they have been debugged by experts, the only really sleuthproof place is a room newly lined with metal and sound-deadening material. Diplomats sometimes hold important conferences in "floated" rooms set up temporarily in a lobby or corridor, or else meet in a freshly inspected room with locked doors and covered windows. Even so, they talk in low voices, and write out all critical words or figures to frustrate undiscovered bugs.

Such precautions ensure reasonable protection-today. But each swift advance in electronics brings new refinements in snooping. There is talk of bugs that probe and communicate by laser light; of infra-red cameras that see through curtains; of receivers that intercept microwave beams, or wring valuable figures from the entrails of computers. In a few more years, the whispers of ambassadors in a floated room may be no safer from prying ears than pillow talk in a resort hotel.

|