SPY-TECH

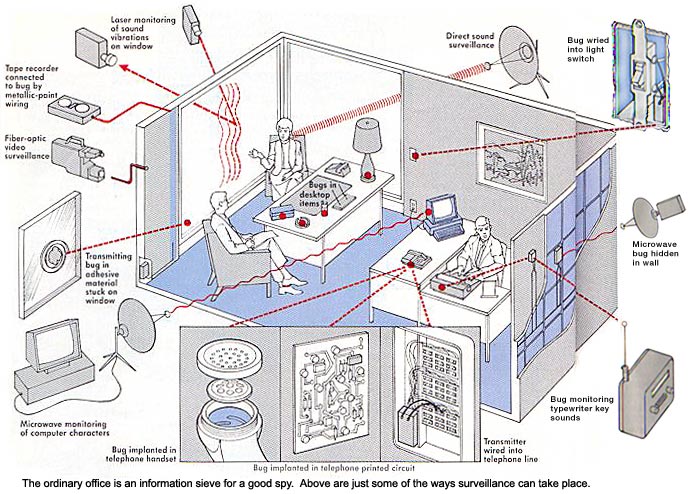

Are your shoes listening to you? Is your lamp watching? Could be.

Eavesdropping technology is now in the hands of the

jealous spouse, the nosy neighbor, and the prying executive.

By Doug Stewart

Discover Magazine March 1988

It's a quiet Thursday evening in Brooklyn. Ray Melucci, private eye, is home alone with his wife. He ruffles through the day's paper. He paces around the house, opening and shutting doors, clearly uneasy about something. "He probably didn't get through yet," Melucci mutters to his wife. She says nothing. In the background, a singer on the radio is making a racket to electric organ accompaniment. It sounds awful.

I know it sounds awful because I'm eavesdropping from 200 miles away, thanks to a device attached to the telephone wire in Melucci's living room. The gadget is called an infinity bug (since you can trigger it from any distance as long as you have a phone). I turned it on by dialing Melucci's number and quickly playing a sort of tape-recorded electronic birdcall into my phone's mouthpiece. In response the bug obediently switched off the ring mechanism in Melucci's phone and switched on the bug's microphone. Melucci's telephone is still resting innocently on its hook, but the phone line is now live. (My snooping would be illegal, except that Melucci planted the bug himself to show me how it works. He's uneasy because he can't be sure if I'm listening or not.)

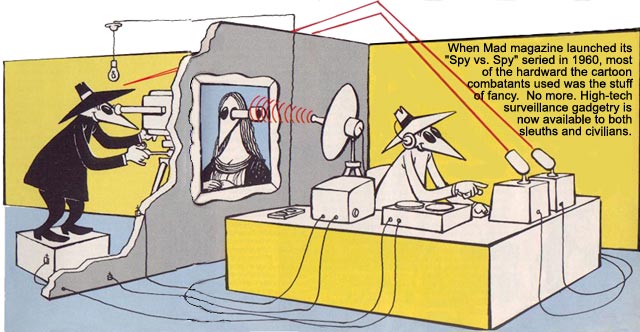

The infinity bug, which sells on the black market for about $1,000, is only one small part of an arsenal of insidious items that people secretly use to watch and listen to one another every day. Once upon a time, hidden microphones and concealed tape recorders were strictly for cops and spies. Today such gadgets - and a host of elaborate and expensive measures to counter them - have filtered down to the jealous spouse, the nosy neighbor, the high-level executive, the local politician.

It's hard to measure how much spying actually goes on, since the snoopers generally stay mum and the targets generally don't know, but there is evidence that it's widespread. A few years ago, when federal investigators posing as executives asked 115 detective agencies in seven cities to tap the phones of supposed business competitors, over a third said sure (for fees ranging from $30 to $5,000). Many of the agencies that did decline the job suggested do-it-yourself phone taps and explained how to install them.

The government is an even worse snoop than the private sector. Although the feds leave it to commercial industry to develop and manufacture most spy-tech hardware, government purchasers are often first in line to grab whatever the for-profit designers come up with. A recent congressional study revealed that one in four federal agencies surveyed are now using some kind of electronic surveillance.

Clandestine listening devices have also turned up on the campaign trail and in the judicial arena. Sparks flew during the 1986 gubernatorial race in Texas when a member of the Republican challenger's staff found a matchbook-size bug in his office hidden behind a needlepoint elephant wall hanging. Even more notorious was last November's mysterious bugging of the office of Harvard University law professor Laurence Tribe. At about the same time Tribe was angering pro-administration Washingtonians by actively battling the nomination of Judge Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, the professor's secretaries noticed that the office telephone had begun acting strangely. On more than one occasion, noises that sounded suspiciously like a third party picking up an extension phone would intrude on routine calls.

The university's telecommunications technician and an outside security expert found nothing in Tribe's phone; however, examining the building's telephone junction box, they discovered a crude five-foot jumper wire attached to Tribe's line. Now, months later, the university still has no proof that the tap was associated with Tribe's anti-Bork activities, but the investigation is continuing. Said the outside security expert: "We found blood on the floor, but no body."

Eavesdropping, however, isn't the only danger that pols, execs, and common folks face. Thanks to fears of terrorism, kidnapping, and good old-fashioned street crime, there has been a surge of interest in "executive defense." A raft of mail-order firms now sell a dizzying range of products designed for both the prudent and the paranoid: protective umbrellas that operate like electric cattle prods; remote-controlled car-ignition systems; telephones that can change a man's voice into a woman's; briefcases booby-trapped with high-voltage electric jolts.

Despite this wealth of multipurpose goodies, the technological heart of the business remains surveillance and countersurveillance. To see what's available, I decided to attend a recent security-technology show in New York.

Among the electrified chain link fences and the promotional videos offering "sensors in every doorway if needed," a sales man from a Tennessee company called Research Electronics shows me a $895 device that resembles a plastic hockey puck with a suction cup on one side. The product's sole purpose is to protect your privacy by making an inaudible high-pitched sound that causes your windows to shake. "Using lasers, some surveillance people can actually pick up the vibrations of a person's voice off a windowpane," the salesman explains. Such a system is a variation on the old tin-can telephone: the laser beam is the string, the window is the bottom of the tin can. By timing the return beam, the eavesdropper can measure slight vibrations of the window and try to reconstruct the conversation that's causing them - provided the window isn't also being rattled by traffic, slamming doors, elevators, or vibrating hockey pucks. The salesman guesses that roughly 2 percent of all eavesdropping is now done by laser, although he concedes he's never run across any hard evidence of its use.

Among the electrified chain link fences and the promotional videos offering "sensors in every doorway if needed," a sales man from a Tennessee company called Research Electronics shows me a $895 device that resembles a plastic hockey puck with a suction cup on one side. The product's sole purpose is to protect your privacy by making an inaudible high-pitched sound that causes your windows to shake. "Using lasers, some surveillance people can actually pick up the vibrations of a person's voice off a windowpane," the salesman explains. Such a system is a variation on the old tin-can telephone: the laser beam is the string, the window is the bottom of the tin can. By timing the return beam, the eavesdropper can measure slight vibrations of the window and try to reconstruct the conversation that's causing them - provided the window isn't also being rattled by traffic, slamming doors, elevators, or vibrating hockey pucks. The salesman guesses that roughly 2 percent of all eavesdropping is now done by laser, although he concedes he's never run across any hard evidence of its use.

Nearby, as burglar alarms at other booths whoop and shriek, a salesman from a New jersey outfit with the lofty title of Law Enforcement Associates hawks voice scramblers, do-it-yourself fingerprint kits, and vials of letter-bomb visualizer (a liquid that makes paper transparent, as salad oil does, but then dries without a trace). I watch as a salesman demonstrates a laser rifle-sight to a man whose name tag identifies him as an administrative attach� to the Saudi embassy in Washington. "This'll put a dot on a person's chest from four blocks away," the salesman says, planting the laser on the temple of an oblivious conventioneer 50 feet across the room. The "administrator" seems impressed.

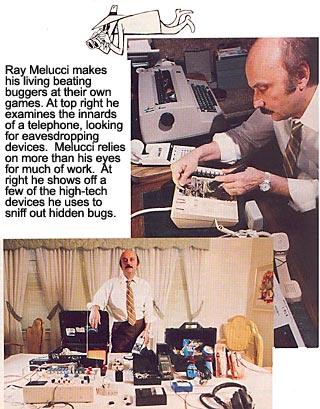

Nowhere do I spot booths offering the electronic eavesdropping equipment I came to see. The reason, I would later discover, is simple: use of such gadgetry by anyone other than a law-enforcement agent is a federal crime, which dampens over-the-counter business. The best way to see what's out there is to talk to someone whose job is not to plant the stuff, but to dig it up. After the show I pay a visit to Ray Melucci, the Brooklyn detective. An anti-bugging expert, Melucci has amassed an impressive cache of sneaky surveillance tools. "For research purpose, of course," he says. "I always say, if you don't know how to put them in, you can't know how to take them out."

The balding, 49-year-old New York native wears a Walther PPKS in a shoulder holster - "James Bond's gun," he points out - and credits his knowledge of bugging basics to a retired burglar he calls Mike the Nose. Melucci runs his business on a single simple credo: Don't ask too many questions of your clients. Many of his customers include people who have just been indicted for various transgressions and have come to him to find out if someone's been listening in on them.

Melucci rummages in his jumbled electronics-filled briefcase and extracts a wireless microphone the size of a pack of Camels. "This will pick up a whisper from fifty feet," he says. Powered by two 9-volt AA batteries, the device can transmit radio signals to an FM receiver over a block away - far enough to reach a hidden listening post or a voice-activated tape recorder. Melucci says this is a popular piece of equipment for police surveillance work. "it's not very sophisticated, but it doesn't have to be," he says. "Most of the people police put under surveillance aren't brain surgeons."

I ask Melucci to describe the smallest wireless transmitter he ever saw. "This one," he says, producing from his briefcase a thin plastic box smaller than a postage stamp. For power the system uses a 1.3-volt hearing-aid battery. The device is so small it could be swallowed whole. Melucci says it can transmit half a block for up to 24 hours before the battery dies. "Most sophisticated buggers wouldn't use something like this, though, because they'd have to go back and change the batteries every day, which is ludicrous," he says. A much better idea is to hard-wire a microphone, either by connecting it to the telephone line, as with the infinity bug, or, less commonly, by tying it into a room's electrical wiring, often behind an outlet or light switch.

"The best way is to use the telephone line," Melucci says. "You use wires that are the right color, and you can put the bug in a plastic casing that says NEW YORK TEL or maybe HIGH VOLTAGE. That keeps people away." Melucci explains that the infinity bug was originally invented as a home security device. People away on vacation could phone home to listen for burglars or teen parties. A client once hired Melucci to install an infinity bug in her Long Island beach house. Later, when he asked if it was working okay, she reported that the sound of the ocean was drowning out the voices in the house. "I said, 'What voices? I thought the house was empty,'" Melucci recalls. "That's when she told me she was using it to listen to her husband and his girlfriend."

In the old days the law was not very picky about such matters. In the 1960s, when transistorized wireless microphones first became bite-size, concealed bugs were all the rage. A Manhattan outfit called continental Telephone Supply Company did a brisk trade selling "investigative accessories" to whoever walked in off the street. Cuff links wired for sound were popular, as were $150 table lamps with hidden transmitters - you gift wrapped the lamp for your quarry and kept the radio receiver for yourself. According to a 1966 Esquire article, Continental's salesmen offered first-time customers discreet suggestions on choice spots to plant a hidden bug. In some situations, they advised, the back of a desk drawer was ideal. In others, the inside of a mattress was more appropriate.

The federal government outlawed civilian use of "attack devices," or concealed transmitters, in 1968. Since then, most security specialists have followed Melucci's lead, going into businesses designed not to invade privacy but to protect it.

Information Security Associates of Stamford, Connecticut, is one such company. The firm occupies a nondescript industrial building whose waiting room has neither a receptionist nor piped-in music, just a locked door without a knob. The company designs and sells devices used to carry out electronic "sweeps" of office buildings. Dick Heffernan, the company's vice president and co-founder, often does the sweeps himself. A genial, bushy-browed, cherub-faced man, Heffernan has been in the countersnoop industry for 20 years. He assures me that business is booming. He numbers among his past and present clients 30 percent of the Fortune 500, including seven or eight of the top ten.

In a windowless classroom down the hall from Heffernan's office, a staffer is leading a training session for a dozen middle-aged students; most of them are corporate-security types here for the week. At the front of the room is a large display board festooned with sample radio transmitters. A bumper sticker affixed to the top of the board reads, HAVE YOU HUGGED YOUR BUG TODAY?

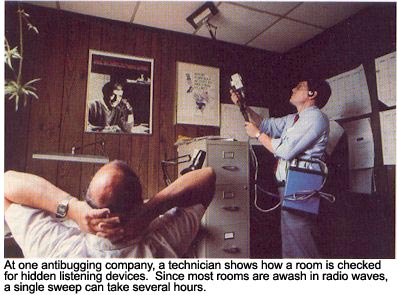

The first step in most sweeps is to check for telltale radio signals that a wireless microphone hidden in a room transmits to a listening post or tape recorder outside. In spy movies the debugging expert strolls around the room waving a radio receiver with a long antenna, all the while watching a meter on the front of the receiver, waiting for the needle to leap into the danger zone. "The magic-wand-type things are a joke," says Heffernan. "Yesterday in class we demonstrated a number of these low-cost pieces, and none of them picked up a simple Radio Shack transmitter." Most rooms, he says, are awash in TV and radio signals, which hide the weak emissions of a carefully tuned bug. The firm's own radio-frequency detector is a heavy desktop console with earphone. It painstakingly sifts through the complete radio spectrum up to 6 gigahertz, well into the microwave band. Sweeping a single room can take hours.

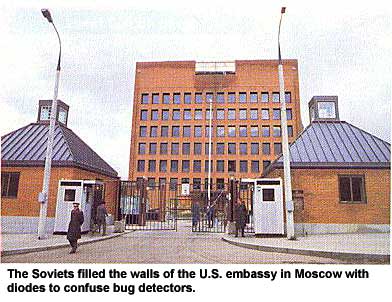

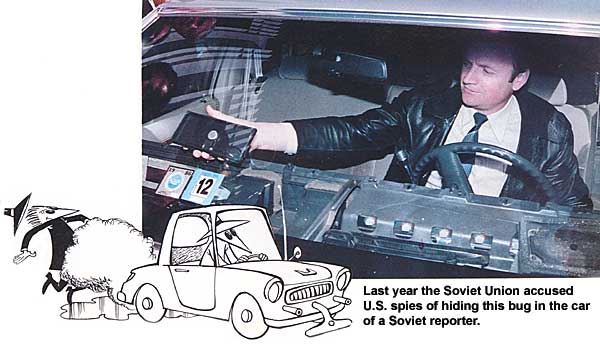

Next comes the phone-tap check. Information Security Associates builds and sells electronic telephone analyzers for detecting suspicious phone-line signals caused by taps. It also manufactures an unwieldy machine called a nonlinear junction detector that searches for any microelectronics that the other two systems might miss. The device, which resembles a vacuum cleaner, emits a steady microwave signal as an operator sweeps the paddle like business end over the floor, a wall, or a piece of furniture. If a tape recorder or transmitter is hidden nearby, its electronic components automatically emit a signal exactly double the frequency of the original signal. The system works whether the snooping devices are turned on or off. It was this kind of detector that the Soviets reportedly tried to counteract by sprinkling thousands of cheap diodes throughout the walls of the new United States embassy in Moscow.

Here in the States, Heffernan's searches have turned up a rich bounty of bugs over the years. Despite his company's high-tech sweep devices, Heffernan makes it clear that in the bug-detecting business there are times when nothing beats the gumshoe's stock-in-trade: the visual search. "I once found a microphone in a conference room wall that had been hollowed out behind the wallpaper," says Heffernan. He found it by snooping around the crawl space above the ceiling, where he noticed a wire that didn't belong. "You go in with a business suit and come out pretty dirty," he says. During a visual sweep of a hotel company's headquarters, Heffernan discovered that someone had rewired a Muzak-type speaker in the ceiling of an executive's office. "if you disconnect the music, the cone vibrates just like a microphone," he says. "It can carry voice signals down the speaker wiring to the listening post outside the secure area" - in this case, an out-of-the-way storeroom. Another time, at a West Coast aerospace firm, Heffernan traced a suspicious telephone line from the general manager's office to a telephone-equipment room on another floor. There he and the general manager found the door open and a telephone lineman's handset swinging from a dangling wire. "That was as close as you get to a smoking gun," he says.

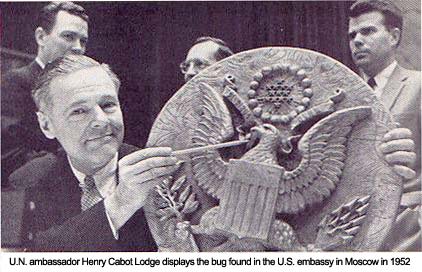

On a wall in the offices of Information Security Associates are photographs of some of the more imaginative bugs in espionage history: a bug planted in the heel of the target's shoe (the batteries were replaced when the shoes were left for shining); a tiny transmitter concealed in drapery material, its thread-thin antenna woven right into the fabric; and, most notorious of all, a listening device found in the U.S. embassy in Moscow in 1952. The hiding place: a hole in the Great Seal of the United States hanging in the ambassador's study. The carved wooden seal, a gift from the Soviets seven years before, held buried inside it a small cylinder called a Hi-Q resonant cavity. The cylinder contained a diaphragm at one end and an antenna at the other. Voices in the room caused the diaphragm and then the antenna to vibrate. U.S. officials surmised that Soviet technicians across the street kept a high-power microwave beam trained on the seal to measure the vibrations, allowing them to reconstruct the conversations.

Like the laser microphone system, in which the target's window is the vibrating surface, this nasty little eavesdropper is known as a passive bug. Passive bugs don't need batteries, wires, telephones or transmitters. As a result, they are nearly impossible to detect. A bizarre variation on the theme is the toilet-bowl bug, proposed by the late Bernard Spindel, a master eavesdropper of the 1950's and 1960's whose career included more than 200 arrests or indictments for illegal snooping. Using Spindel's system, a spy on the roof of a building would place a microphone inside the air-vent pipe leading to the target toilet. Since the surface of the water in a toilet vibrates like a diaphragm in response to nearby voices, and since water is such an excellent conductor of sound, the voices would be carried up the pipe to the microphone.

Among passive bugs, the laser mike has undoubtedly been the most discussed and the least observed - that is, until last October, when Radio-Electronics published a cover story showing how to build one yourself, step-by-step ("Laser Listener: Use a Light Beam to Listen In to Anything, Anywhere, Any Time").

While tinkering with such systems may be legal, using them is not; the government has outlawed laser listening devices for both the hobbyist and the professional eavesdropper. But even with this hardware banned, the industry still has plenty of room for countless other types of spy and counterspy gadgetry. After Continental Telephone Supply was forced by federal law to stop selling bugs in 1968, its founder, Ben Jamil, launched a new firm called Communication Control Systems that specializes in "privacy, security, safety, and survival." The company claims annual sales of between $20 million and $30 million, thanks in part to its chain of seven counterspy shops.

Customers at the stores can try on bulletproof raincoats and practice turning briefcase tape recorders on and off by nonchalantly flipping the handle. When I visit the Third Avenue branch in New York City, a salesman shows me a $2,200 body tape recorder the size of a pocket calculator. He refers to it as an Executive Investigator Kit. "You hook the microphone switch under your watch, and the wire goes up the sleeve of your sport jacket," he says. The wire leads to a pen protruding from a recorder concealed in the shirt pocket. "You turn the tape recorder on or off by moving the pen up or down," he says, demonstrating. The maneuver strikes me as a conspicuous one, but I suppose that's what make the game exciting. Communication Control Systems does a brisk business in these recording systems, in part because they have not been regulated the way transmitters have. As long as you're in the room with the device and are a party to the conversation, the law doesn't give a hoot what you record.

But tape recorders - however they're concealed - are perhaps the least glamorous offerings in the company's inventory. "These over here" - the salesman waves at a row of typewriter-size machines - "are all voice stress analyzers. They measure subaudible microtremors in your voice, which are involuntary responses to stress. If you're under stress, it usually means you're lying." Unlike conventional lie detectors, he says, these can be hooked up to a phone or a tape recorder. Subjects never know they're being tested for fibs. The machine is nothing if not user-friendly; on its digital reading, 20 is truth, 40 is a lie; it's that simple. "You can find out who your friends are or if your wife's been cheating on you," the salesman says. "It's the greatest invention since television."

Voice stress analyzers, which cost between $4,000 and $11,000, are among the industry's perennial best-sellers. Critics complain that they're unreliable, the lazy man's polygraph. Courts won't accept their findings as evidence, and several states have banned their use in job interviews. (On a recent episode of Miami Vice a Colombian cocaine dealer used one while asking his girlfriend if she'd slept with another man. When she hisses "No!" he looks at the readout, pulls out a gun, and shoots her. Since hissed speech contains no microtremors, the coke dealer apparently misread his equipment.)

At Communication Control Systems' world headquarters in Port Chester, New York, Mike Kelly, head of the company's surveillance-technology group, leads me past the racks of consumer gadgets to a special law-enforcement showroom and closes the door. Kelly, who has since moved to the company's Paris office, is a stocky, tough-talking former Treasury agent in his late 30s who describes himself as an expert in antiterrorism and narcotics trade. He hands me a weird looking pair of $12,000 night-vision goggles. The room is dark, but when I strap on the goggles I see a luminous green image of even the darkest corners. This is no trick; a battery-powered photomultiplier behind the two lenses can boost the amount of light entering the goggles up to 40,000 times. "I've flown a plane at night with these," says Kelly. "No problem."

Next he shows me the smallest video camera I've ever seen, priced at $2,500; the body is an inch-and-a-half square and perhaps an inch thick, the size of a small box of wooden matches. Beside this is an even more impressive device. It looks like a car antenna, but Kelly points out a pinhole near the top. Behind the pinhole is a tiny wide-angle lens. Stretching down inside the antenna is a fiber-optic cable attached to a large box containing a video camera and transmitter. I realize the antenna is rotating almost imperceptibly. "It's for stakeouts," says Kelly. "You set it up on a car where the antenna would be." An open briefcase containing a receiver and a small TV screen rests on a windowsill nearby. In practice, the screen would be monitored inside a second car down the street. I watch as a sharp panoramic view of the room sweeps slowly across the tiny screen. "It's not a standard TV frequency," says Kelly. "You don't want people picking this up in their home." I'm ready to buy, but the price tag is $26,000.

For an even bigger spender Communication Control Systems offers a variety of armor-plated limousines. Its top seller at the moment, priced from $50,000 to $125,000, is a bulletproof BMW whose options include machine-gun ports, tear-gas ducts, an oil-slick emission system, a bomb sniffer, and infrared headlights. The company claims to sell 40 or 50 armored cars a year; most go to Latin America.

The bigger the spy biz grows, the hungrier the general public becomes for information on the newest ways to close the prying eyes. One who satisfies the need is Jim Ross, an expert on communications security, in Adamstown, Maryland. Ross runs antibugging seminars designed to teach security personnel how to protect themselves from everything from laser listeners to letter bombs. Ross likes the low-tech approach to problem solving. (In his newsletter, he advised readers to save money on letter-bomb visualizer, which retails at $4 an ounce, by using freon instead, at eight cents an ounce.)

Ross has conducted hundreds of bug sweeps nationwide, and though bugging equipment has grown more and more sophisticated, he has found that if you're worried about being spied on, the first place to look is your telephone. Nothing, it seems, beats the old standby in eavesdropping popularity. "I found one here in the Washington, D.C. area just a few weeks ago," he says. Some frugal soul had altered the mouthpiece of a conference room telephone by wiring a 9-volt battery to the phone's own microphone and attaching it to a spare set of wires that phone lines normally contain. The new connections bypassed the phone's hook switch, which is what breaks the circuit when the handset is hung up. The phone had therefore been live on the hook, sending continuous room sounds to the eavesdropper. Ross traced the line to the office of a lower-echelon employee who was presumably curious about what the big boys discussed behind closed doors.

Ross admires that kind of initiative. "All you need is the telephone's own microphone and a couple of tiny bits of wire that don't cost you anything, as opposed to some Rube Goldberg thing that costs a fortune," he says.

Still, Ross understanding the appeal of high-tech gadgetry, the glitzy attraction of teeny transmitters and laser mikes. As a businessman, he deals in the high-tech stuff himself. He offers to sell me a bug that transmits at 10.525 gigahertz, a frequency that even Dick Heffernan's equipment can't pick up. The signal is so information packed, he says, that it can carry not only audio but a live color TV picture as well. All this, and the bug is only six-tenths of a cubic inch. "That's smaller than the nine-volt battery that powers it," Ross says. For $40,000 the whole package could be mine.

I muse for a moment about what secrets I could unearth with an audio-video bug half the size of a walnut. The possibilities are tantalizing. Suddenly, however, an image flashes through my head of a future world in which every shirt button is a TV camera and every microchip a microphone. I tell Ross I'm not quite ready for all this.

Writer Doug Stewart specializes in science and technology.

|