Passing the Bug

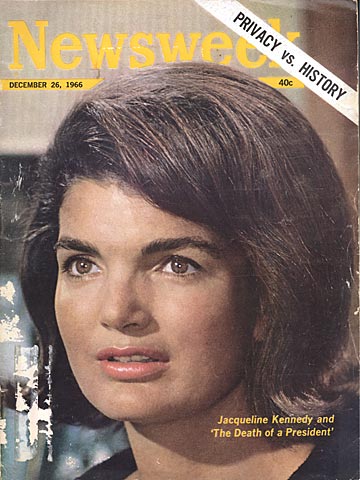

(Newsweek December 26, 1966)

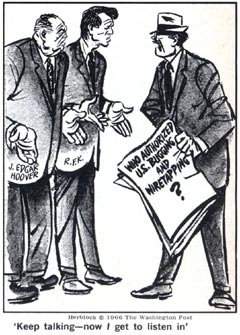

For years, the bad blood ran silent and deep between Robert F. Kennedy and J. Edgar Hoover, with only an issue lacking to turn their cold war hot. The issue surfaced last week--the bubbling controversy over electronic eavesdropping by Hoover's FBI. And sure enough, the private feud went public. The two titans put on a weeklong show of bug-passing that did little credit to either man and managed to avoid the central concern about tapping phones and wiring rooms: not whodunit but when--or whether--it ought to be done at all.

Hoover, for months, had sat simmering while a series of FBI-made cases were blown up or threatened by Justice Department disclosures of illegal electronic spying (Newsweek, Dec.12). With still more cases under review, Hoover, so insiders said, began trying to get word into the press that the rap properly belonged not to him but to his ex-boss, Kennedy. He had only limited success until, in response to a pat letter from Republican Rep. H.R. Gross of Iowa, the FBI chief backed the charge with his name and his considerable prestige--and landed it on front pages across the U.S.

Who and How? By long practice, said Hoover, the FBI had tapped telephones only with the express, written consent of the Attorney General. Kennedy conceded that point; the real issue was the thornier question of hidden mikes, which (unlike telephone taps) are not illegal--unless, as is usually the case, planting them involves trespassing. "Mr. Kennedy," Hover wrote, "...exhibited great interest in pursuing such matters ... He was briefed frequently by an FBI official regarding such matters." While he claimed the "authority of the Attorney General" for bugging as well as wiretapping, Hoover's well-chosen words avoided the matter of whether Kennedy was ever told whose rooms were being bugged when and by what means.

It was on this point that the debate turned. Bobby, backed by a unanimous chorus of old Justice Department colleagues, insisted Hoover hadn't cleared a single bugging device with him and, as a result, he didn't know what was going on. "Absolutely inconceivable," snorted Hoover. "Nonetheless true," replied Bobby. The two spent the week swapping documents, Hoover's suggesting that Kennedy knew about and approved bugging at least in general terms, Kennedy's indicating that he wasn't told about specific cases--and that he had, in fact, issued a 1962 directive barring any "improper, illegal and unethical" investigative methods.

It was on this point that the debate turned. Bobby, backed by a unanimous chorus of old Justice Department colleagues, insisted Hoover hadn't cleared a single bugging device with him and, as a result, he didn't know what was going on. "Absolutely inconceivable," snorted Hoover. "Nonetheless true," replied Bobby. The two spent the week swapping documents, Hoover's suggesting that Kennedy knew about and approved bugging at least in general terms, Kennedy's indicating that he wasn't told about specific cases--and that he had, in fact, issued a 1962 directive barring any "improper, illegal and unethical" investigative methods.

Protocol: The flap had deep roots in the frictions between the two beginning when the Kennedys took office. Hoover, by long tradition, was accustomed to bypassing his nominal boss, the Attorney General, on big questions and reporting directly to the President. But JFK's Attorney General happened to be his brother as well, and Hoover had to deal with Bobby--a bit of protocol he continued precisely as long as JFK lived. As AG, moreover, Bobby was sandpapery rough about what he considered to be gaps in the FBI's intelligence about organized crime. One old Justice hand said the FBI only stepped up the practice of bugging syndicate criminals under Kennedy's gung-ho prodding for more and more data. Bobby got his data--without knowing, by his own account, where he got it. "I was in his office earlier this year," said William G. Hundley, chief of Justice's organized-crime section from 1958 till last September, "and he asked if I knew about the illegal activities. I told him I did. He said, 'Why didn't you tell me?' I said, 'I wasn't aware of their scope, Bob. I thought you had put your John Hancock on them'."

While the flap over government snooping ran inconclusively on, a New York grand jury wound up a 27-month investigation of private electronic espionage by indicting 28 persons from Connecticut to California--mostly private eyes and electronics experts--on eavesdropping charges. The New York DA's office said most of the cases involved industrial spying and divorce cases--though the prime catch, once-convicted wiretapper John G. (Steve) Broady, was charged, among other things, with grand larceny for charging one firm $1,500 for removing some nonexistent bugs from its offices. Three suspects, authorities noted wryly, made a sideline of writing and lecturing--against the evils of wiretapping.

|