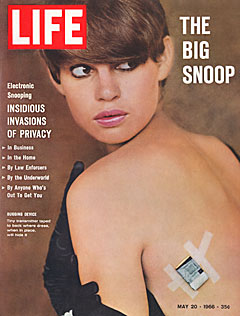

The Big Snoop

Electronic Snooping - Insidious Invasions of Privacy

Life Magazine - May 20, 1966 - John Neary

• In Business

• In the Home

• By Law Enforcers

• By the Underworld

• By Anyone Who's Out To Get You

This article is reproduced in it's entirety, including photographs with captions.

|

|

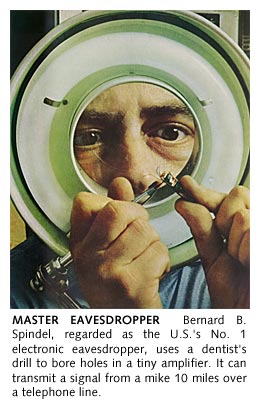

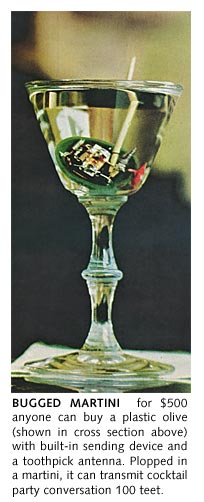

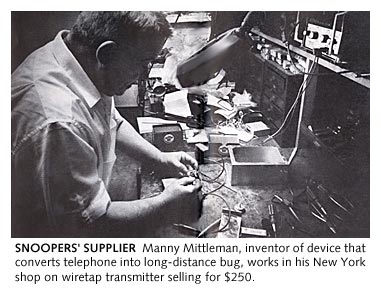

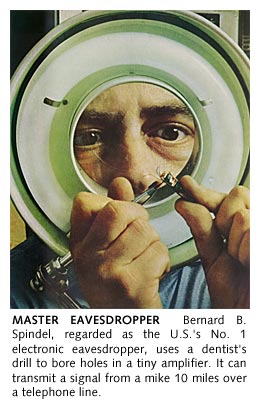

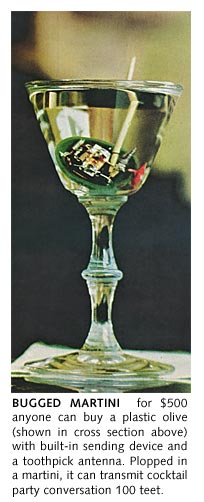

The man on the opposite page (right), peering through an illuminated magnifying glass as he assembles a tiny bugging device, is a specialist in the multi-million-dollar industry of eavesdropping. Without the slightest awareness on the victim's part, this handiwork may wind up in the olive of a nearby martini, in the mouthpiece of his telephone, in a knob on his car's dashboard, in the handle of his briefcase, even in a cavity in the tooth of an intimate associate. It will pick up what he says, amplify it and transmit it word for word to tape recorders that sometimes are situated hundreds of miles away. Despite the protection against invasion of privacy afforded by he fourth Amendment to the Constitution, bugging is so shockingly widespread and so increasingly insidious that no one can be certain any longer that his home is his castle - free of intrusion.

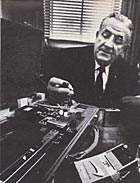

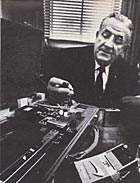

Senator Edward V. Long (Dem. - MO), whose Senate Judiciary Subcommittee has been holding intensive hearings on invasion of privacy by government agencies, has charged that "Federal agents are embarked on a nationwide campaign of wiretapping, snooping and harassment of American citizens." The government has been electronically spying on its citizens for years. The Internal Revenue Service, for example, has admitted bugging public and private phones and even rooms where IRS auditors called businessmen for questioning, on the theory they might reveal something when IRS men left the room. |

SENATE INVESTIGATOR. Senator Long inspects an attaché case rigged with receiver, voice actuator and tape recorder. At right foreground is kit's transmitter that fits into a cigarette pack.

|

Federal agencies and police operatives at least can argue that wiretapping and bugging are helpful aids in the enforcement of the law. But that justification does not exist for the growing legions of private citizens - businessmen, union officials, employers, suspicious spouses - who find it ridiculously easy to indulge in electronic spying. They can choose from a vast array of inexpensive, easy-to-install snooping devices which can be bought over the counter with no questions asked. On these pages LIFE reveals in detail this electronic assault on privacy, the murky legal problems that are involved and the phenomenon which long before Orwell's 1984 presages what Senator Long has called "a naked society, where every citizen is a denizen in a goldfish bowl."

|

|

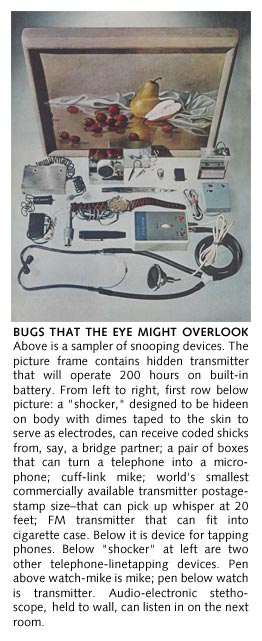

THE MINIATURE TOOLS OF THE EAVESDROPPER'S TRADE

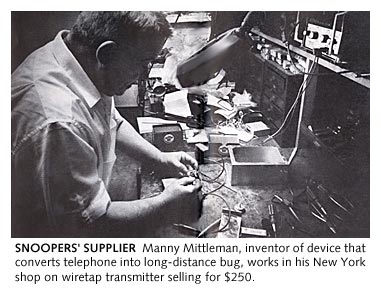

Electronic eavesdropping owes its boom to the invention of the transistor and the printed circuit which made miniaturization possible. As manufacturers leap-frog each other in turning out ingenious new refinements, the components they sell have been getting smaller and more efficient. One item they offer, for example, a Dick Tracy-style wristwatch microphone, is downright cumbersome compared with other mikes that are as small as sugar cubes.

Laws with Ambiguity

The technology of snooping has so outdistanced the law that controls are all but nonexistent. A new FCC regulation, adopted only last month, bars to all but law enforcement agencies the use of radio devices to transmit or record conversations without the consent of all parties. But this is a purely a government regulation lacking the hard force of statutory law. There are no federal statutes on eavesdropping and only one that deals specifically with tapping telephones. This is Section 605 of the Communications Act of 1934, and Attorney General Katzenbach says that today "it would be difficult to devise a law more totally unsatisfactory."

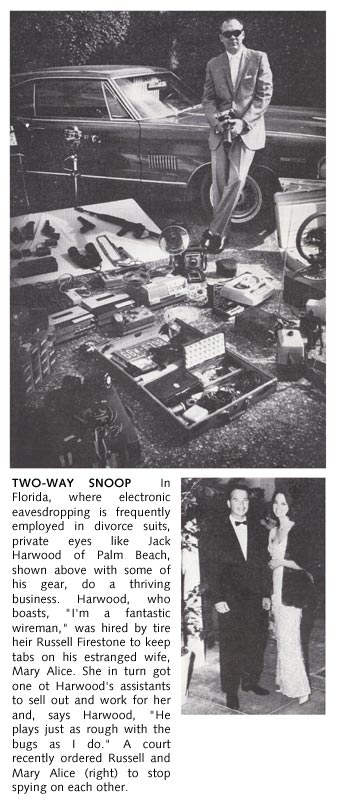

State laws add to the confusion. Eight states (Pennsylvania, Illinois, Wisconsin, Kentucky, California, New Jersey, Florida and Michigan) ban wiretapping altogether. One, Louisiana, permits only law officers to tap phones. Five states (New York, Oregon, Maryland, Nevada and Massachusetts) allow tapping under court order. In all the rest, the issue has been ignored or the laws are open to inconclusive interpretation.

In general, law enforcement agencies are restrained by the uncertainty that evidence obtained by electronic snooping will hold up in court. Evidence uncovered by wiretapping has been held to be "tainted" and therefore inadmissible in a federal trial. Courts have further ruled electronic eavesdropping evidence is admissible only if it was not the result of a trespass on the property of the subject. In the 1963 Lopez case, the Supreme Court ruled that a tape recorder hidden on the person of an investigator did not itself constitute a trespass and that tapes obtained were admissible evidence.

Private citizens who go in for electronic eavesdropping do pretty much what they can get away with, which is plenty. When the chairman of the board of the Schenley Corporation found listening devices in his office last year - presumably installed by a competitor - there wasn't a great deal he could do except rip them out. Senator Long believes the best solution is a law requiring licensing of all bugging equipment. But the particulars of such legislation remain vague - especially since every transistor radio is crammed full of components that any expert can turn into a bug.

ON AN ASSIGNMENT WITH THE ACE OF THE BUGGING BUSINESS

by John Neary

Each day Bernard Bates Spindel rises to face the heady challenge of living yet another episode in the life of his favorite character: Bernie Spindel--expert pilot, consummate lock-picker, foreign adventurer, electronics wizard and the No. 1 big-league freelance eavesdropper and wiretapper in the U.S.

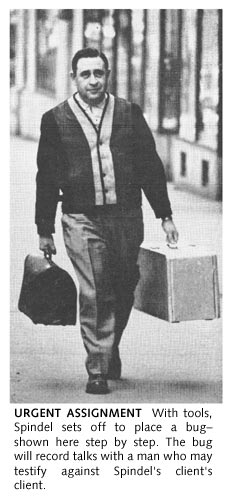

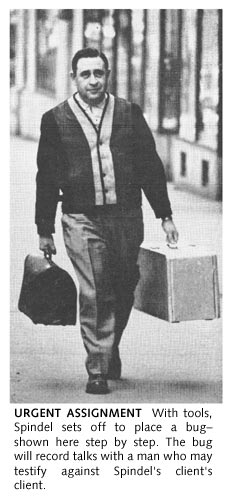

On this particular Saturday morning the limp 6-foot, 210-pound sack of a man ambled out of a gray clapboard house in upstate New York, filled up the trunk of a Lincoln sedan with tools and gear from an inventory of 3,000 electronic components, slumped himself in behind the wheel and set off for a few brisk hours of hard work in the city. It would bring $350.

Both the underworld and law enforcement admit Spindel is the best in the business. Jimmy Hoffa, who should know, calls Bernie and expert technician.

|

|

"I have no doubt," says a government prosecutor who has more than once locked horns with him, "that if Spindel wanted to tap my phone, he could--and for all I know, he has."

"I'm a private practitioner," Bernie says earnestly, "and I work for anybody who wants to find out if anybody's on 'em, and I don't ask for a pedigree." He will not work for law enforcement agencies, and he says he will not knowingly break the law--or Bernard Spindel's conception of the law. In the end, Bernie says, "It's not what you do, it's what you get caught doing." In short, Bernie sees himself as a sort of latter-day transistorized Robin Hood of privacy invasion.

His impressive letterhead lists some eight separate security services. It mentions not a word about offensive tactics like tapping employee phones to check for leaks. Bernie handles that sort of thing too.

On this particular day Bernie had three stops to make in Manhattan. His first was in Spanish Harlem, where he met a short, flat-featured man in a black raincoat. They walked together around the corner. A few minutes later Bernie, hustling now, got back in the car and headed for a cafe in the downtown Italian district--a "Mafia handout." After a 2 1/2 hour search for police-installed microphones or wiretaps (he found none) Bernie headed uptown.

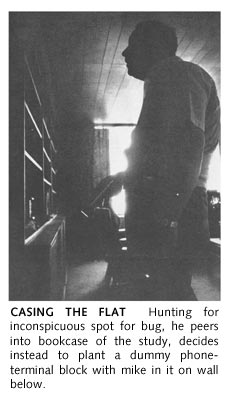

He rolled the Lincoln to a gentle stop on West 57th Street and double-parked. Soon a detective friend climbed into the back seat of the Lincoln. Quickly he sketched the floor plan of a nearby flat where a conversation was to be bugged.

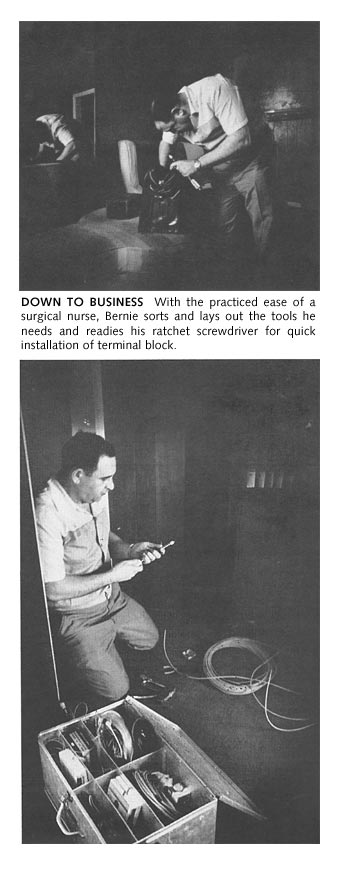

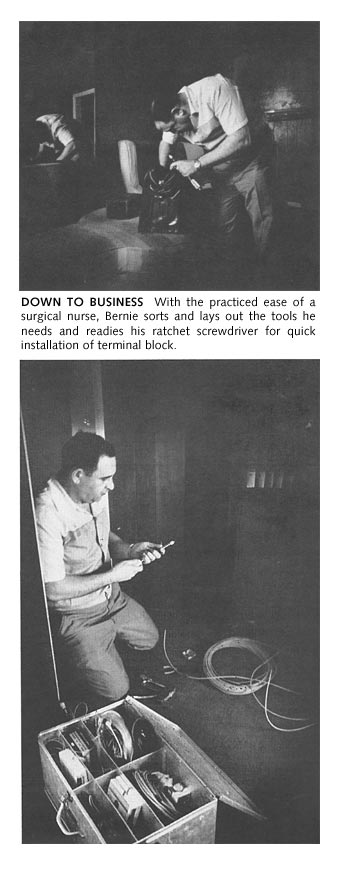

Out of the trunk Spindel took an aluminum box, two recorders and the black briefcase that goes with him on every job. In the briefcase is an incredible paella of paraphernalia, from a standard phone company tone generator to lock pick.

|

|

|

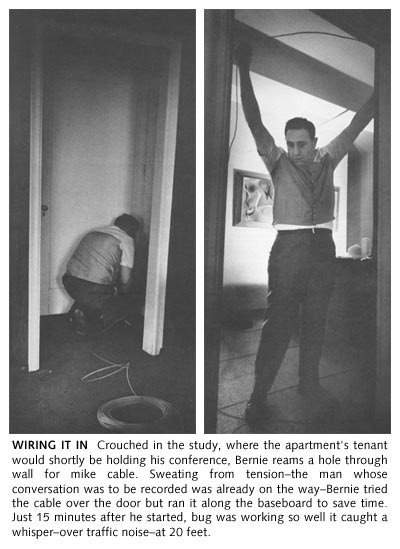

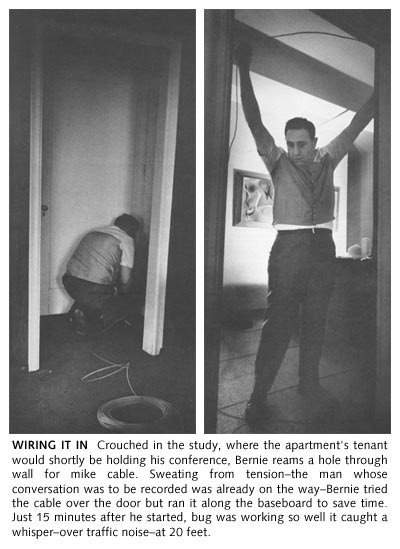

The Lincoln was parked in a nearby garage, and Spindel and the detective went up to the apartment. This client, said the detective, was involved in a little tiff with a government agency. A friend of the client was going to have a chat right here with a man who might give crucial testimony at a forthcoming hearing. A tape of this conversation might bean advantageous thing to have. Bernie set swiftly to work.

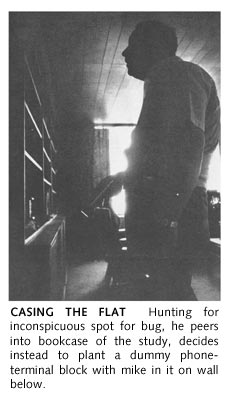

Time was short, so the installation was relatively unsophisticated. "It isn't the device so much as it is the use of imagination on where to put it," says Bernie. "What I care is, when I get a call to go out and do something, I do it."

Driving up to Central Park West a short time later, he scanned the buildings along the West Side almost lovingly. "I've done a job in at least one building in just about every block along here. Sweet and luscious on the outside, but you find out what really goes on�"

Bernie prodigiously tapped his first phone at age 12. It was a pay phone in a tenement hallway. Bernie could hear it all from earphones in the coal bin. "It began to give me a very peculiar feeling of power, to know what everyone in that building was saying and what they were doing. I've never lost the feeling. I have knowledge that no one else in the world has about certain individuals�"

|

Bernie was in the Signal Corps during World War II, and after his discharge he quickly found himself handling wiretap jobs for New York City detective agencies.

His work, mostly matrimonial and business investigations, went well. Then, through a series of influential jobs, he as recommended to James Riddle Hoffa, a Detroit Teamster official who needed some work done. For actions stemming from this notable liaison, Bernie was brought to trial with Hoffa four years later on a charge of conspiring to wiretap. Both men ultimately were acquitted.

Spindel's refusal to go against Hoffa, in this case and thereafter, has produced a mixed yield. On the one hand, he feels he has been mercilessly badgered by government agencies. On the other, business has flourished, for Bernie has won the respect of the fink-wary underworld, whose patronage pays well. "I could make ten calls right now," he says, "and, I guarantee you, I'd have $100,000 in cash by noon tomorrow. Interest? None."

As his contacts improved, Bernie branched into foreign work. He can spin endless bizarre yarns such as the one about throwing "a top agent of Trujillo's secret police" out of a second-story window in Santo Domingo (after jamming the slide of the agent's automatic with his thumb).

Today, he says, "if a man like Hoffa, or a foreign government, or an underworld character calls me for a confidential mission, they know it will remain confidential. The ability to maintain a confidence is the one attribute they respect."

Jimmy Hoffa takes a somewhat less fulsome view of Bernie's ethical reputation. "A copper's a copper," says Hoffa of Bernie. "Any kind of cop or investigator, you've got to figure that anything they find out they're going to sell to somebody else. But you hire a guy like this to tell you, and you don't tell him nothing."

Whatever the esteem in which his clients hold him, Spindel claims to have a vault full of vital tape recordings within easy access of his beneficiaries, just in case his confidence should prove to be poorly placed. "just say I'm well insured," he says.

|

|

Spindel has about 35 reasonably steady customers. In addition to his underworld customers, he does work for a discount merchandising firm for which he installed hidden cameras, a cosmetics firm fearful of losing trade secrets, and assorted unions who call him on a per-crisis basis. He also serves as consultant to several firms engaged in manufacturing security products like cameras and alarms.

Spindel has about 35 reasonably steady customers. In addition to his underworld customers, he does work for a discount merchandising firm for which he installed hidden cameras, a cosmetics firm fearful of losing trade secrets, and assorted unions who call him on a per-crisis basis. He also serves as consultant to several firms engaged in manufacturing security products like cameras and alarms.

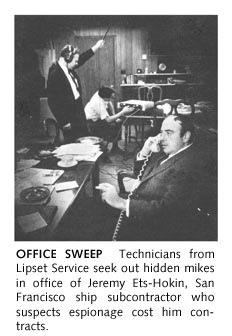

What, exactly, does a "search" of your premises by Bernie Spindel consist of? That depends on who might be after you. If it's just another private eye or the local cops, Bernie can service you out of his car trunk. If it's the FBI or the CIA, though-that's something else, calling for Bernie's big mobile lab and a dazzling checklist of electronic procedures. Similar methods were employed by Spindel in connection with the celebrated jury-tampering trial of Jimmy Hoffa and others in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Spindel was called in during the trial by the defense lawyers who, seeking grounds for an appeal, wanted a complete check on any government surveillance of defendants and their attorneys. Bernie set up shop in the Patten Hotel and began a complete security sweep of rooms occupied by the Teamster defendants. He quickly picked up what he was sure were FBI signals from a nearby transmitter and proceeded dutifully to make recordings. He later swore that caution had prevented him from making a complete trace for phone taps. The instruments used for such a check were the same as those employed in actually tapping a phone, and he didn't want to risk getting caught and giving anybody the wrong idea. In part, this wariness had been induced by messages intercepted from the FBI transmissions. "I think we are tuned in," went on FBI broadcast. "That's probably Bernard. Hiya, Boyney, Bernie�Making lots of money working for Mr. H?�Go home, Bernard."

Spindel's FBI recordings and Spindel's testimony were a part of a subsequent move for a mistrial by the defense, but they failed to convince the courts that the FBI was engaged in improper surveillance.

Still, Bernie had kept proudly intact his record of never missing a tape or a picture.

An inspection for a major commercial client follows similar meticulous patterns. A complete sweep of company offices, labs and conference rooms takes Bernie and an assistant two or three days and costs the client around $2,500.

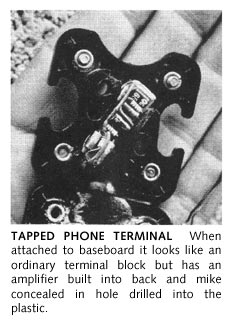

Spindel talks proudly of mikes he has pulled out of mobsters' walls. He recently discovered "an FBI-installed" terminal block microphone in the office of a Mafia chieftain. How did he know it was FBI? "That's like saying, for an artist in the jewelry field, he can look at a piece of work and know who did it. It was too sophisticated for the police department, way over the heads of the D.A.'s office, certainly not the state police-it had to be made by somebody who knew what he was doing." In this case, who else?

At home, Bernard Spindel is an accomplished barbecue chef, a horse fancier, builder of floating electric Christmas trees, husband, father of seven children and instructor of 4-H Club members on the subjects of photography, horsemanship and, of course, electricity. He designed his comfortable house-with a few bugs planted here and there in the walls. He buys the family meat by the thousand-pound load. The seven children share four ponies, three dogs and two cats. His svelte wife, Barbara, ferries the kids around on Saturdays to the movies and teaches 4-H Club girls how to sew.

Mrs. Spindel is also the chief executive of B. R. Fox, which is the company that owns the whole Spindel snooping operation. The Lincoln, the lab, the house, the inventory of parts-none of it belongs to Bernie, who legally holds title to little more than the Waltham wristwatch with Jimmy Hoff's picture engraved on the back (Jimmy gave it to him for Christmas).

What he needs to do a job he requisitions from B. R. Fox (Barbara's maiden name), paying for it out of the proceeds of the job. A $2,000 inspection for a longshore union leader might yield Bernie only $500 walking-around money-the rest going to B. R. Fox for rental of equipment. It seems an enviable arrangement-one that could be calculated to pique the curiosity of the Internal Revenue Service. Government sources acknowledge ruefully, however, that after three years of investigation, Spindel has come up virtually judgment-proof in this regard.

Bernie stays reasonable loose, varying his routine, taking different routes to New York, seldom catching the plane he made reservations for, checking over his house and car every so often with his search receivers, using pay phones (never the same one twice in a row) for important calls, always checking with his lawyers before a doubtful job. Such prudent living has largely kept him out of the soup.

He has been indicted or arrested 204 times-all but twice for offenses connected with snooping-and beaten every rap but one. A jury in Springfield, Mass. recently found him and a co-defendant guilty of eavesdropping. The fine, $500, has been suspended pending a review.

Meanwhile, Bernie is now looking jauntily ahead to littler and better bugs. Already, he chortles, he's doped out a way to tap the forthcoming video-phone, jumping the circuitry in such a way that he'll be able to see right into the subscriber's home.

The subscriber, as usual, won't be able to see Bernie.

|

Spindel has about 35 reasonably steady customers. In addition to his underworld customers, he does work for a discount merchandising firm for which he installed hidden cameras, a cosmetics firm fearful of losing trade secrets, and assorted unions who call him on a per-crisis basis. He also serves as consultant to several firms engaged in manufacturing security products like cameras and alarms.

Spindel has about 35 reasonably steady customers. In addition to his underworld customers, he does work for a discount merchandising firm for which he installed hidden cameras, a cosmetics firm fearful of losing trade secrets, and assorted unions who call him on a per-crisis basis. He also serves as consultant to several firms engaged in manufacturing security products like cameras and alarms.