| Home | Info | About Us | FAQ | Contact Us |

The Battle of the Bugs

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Knowledgeable officials have several explanations for what went wrong. One theory, widely shared by conservatives both in and out of government, is that the State Department has always been lackadaisical about espionage and embassy security.

Security experts, on the other hand, say the lack of careful oversight of the new embassy's construction is at least partly due to perennial congressional pressure to hold down costs.

But all sides seem to agree that the 1972 U.S.-Soviet treaty contained a fatal flaw-a requirement that both governments use local contractors to build their new facilities. "The White House under Henry Kissinger forced us to do that," one U.S. official says bitterly-for that simple stipulation, most observers agree, was the opening wedge for the KGB. (In a television interview last week, Kissinger said he could not recall the details of the 1972 agreement.)

Construction began in 1979. The Soviet contractor insisted on prefabricating most of the chancery building's concrete structural components away from the building site, which is common practice in the Soviet Union. Although U.S. experts were present at all times, sources say security supervision was poorly coordinated, and U.S. counter-spooks did not inspect the plant where the concrete beams and panels were being poured. In 1983, after the U.S. team belatedly began to X-ray the concrete structure for flaws and bugs, the entire Soviet labor force walked off the job to protest what they said was a health hazard to workers. The dispute was resolved and construction continued: by 1985 the chancery's structural shell was complete. At that point Washington sent in another debugging team, and a huge array of microphones was detected in the structural concrete. The bug network covered the most sensitive area of the eight-story chancery building, a windowless floor that was obviously intended for secret operations. Though the bugging technology was not new, U.S. experts were stunned by the size and subtlety of its installation; clearly, the new chancery had been compromised on a massive scale.

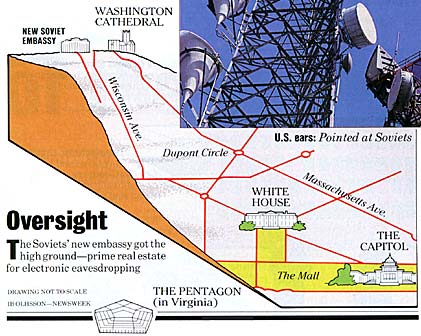

Comradely control: Soviet officials made none of these mistakes in Washington. Although it is true that the site of their new embassy came about almost by accident-the Soviets initially wanted to build in suburban Chevy Chase, and it was the U.S. government which found the location that was finally used-embassy officials took extraordinary care to prevent U.S. bugging. They insisted on the use of solid, rather than hollow, concrete blocks and refused to accept concrete slabs that had been cast off-site. According to the project architect, they paid an extra $180,000 to have windows and window frames taken apart and inspected, and they paid an extra $50,000 to have structural steel delivered on a schedule that allowed them to X-ray each piece for bugs the night before it was erected.

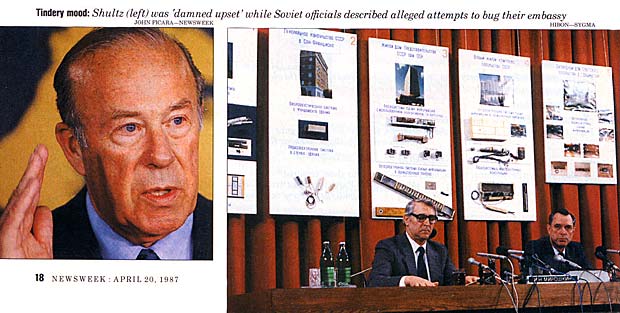

They found some. Knowledgeable sources say U.S. intelligence agencies tried to seed the apartment complex in the new Soviet compound with listening devices in 1979-and in 1980 Soviet officials filed a formal protest with the State Department after some of the bugs were found. Last week, with the embassy wars heating up, Soviet officials called two different press conferences-one in Moscow and the other in Washington-to display what they said were bugging devices removed from their diplomatic posts in the United States. In Washington, Soviet officials led reporters on a walking tour of the new embassy compound to point out where U.S. bugging devices had been found. The embassy security officer, Vyacheslav Borovikov, obligingly scrambled up on scaffolding to pose for photographers with a mysterious black tube that was said to be the battery for a listening device. Another embassy official beamed. "This is glasnost in action," he said-a joking reference to the Politburo's campaign for greater candor in Soviet society.

They found some. Knowledgeable sources say U.S. intelligence agencies tried to seed the apartment complex in the new Soviet compound with listening devices in 1979-and in 1980 Soviet officials filed a formal protest with the State Department after some of the bugs were found. Last week, with the embassy wars heating up, Soviet officials called two different press conferences-one in Moscow and the other in Washington-to display what they said were bugging devices removed from their diplomatic posts in the United States. In Washington, Soviet officials led reporters on a walking tour of the new embassy compound to point out where U.S. bugging devices had been found. The embassy security officer, Vyacheslav Borovikov, obligingly scrambled up on scaffolding to pose for photographers with a mysterious black tube that was said to be the battery for a listening device. Another embassy official beamed. "This is glasnost in action," he said-a joking reference to the Politburo's campaign for greater candor in Soviet society.

Dogs, ponies and skeletons: Glasnost or not, it was good public relations-a propaganda dog-and-pony show that emphasized the point that the United States, like the Soviet Union, has a few skeletons in the closet. The United States, by comparison, seemed to be avoiding any detailed presentation of the extent of Soviet bugging, probably because U.S. spooks don't want the Soviets to know just how effective their counterbugging techniques really are. Nevertheless, the Reagan administration seemed to be losing the propaganda contest.

The broader issue was whether, as Soviet spokesmen repeatedly charged, the Reagan administration was raising the espionage issue in order to cloud the prospects for a new agreement on the control of nuclear weapons. White House chief of staff Howard Baker denied the charge, and Reagan, in an otherwise tough speech delivered in Los Angeles, nevertheless voiced his hope for "a breakthrough" on reducing both sides' arsenals of intermediate-range missiles. The message seemed to be that Washington was determined to make an issue of Soviet espionage in Shultz's talks with Shevardnadze-and let the chips on arms control fall where they might.

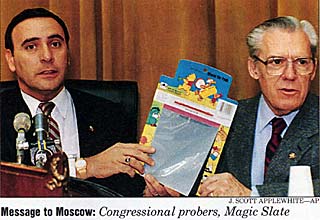

That the Shultz-Shevardnadze talks would proceed amid the renewed embassy wars only heightened the surreal ambience of the whole affair. Somehow the two superpowers were trying to conduct nuclear diplomacy while their governments played a raucous game of so's-your-old-man. But the tortuous business of arms negotiations seemed destined to go on-even if it had to be conducted on the U.S. Embassy's now infamous Magic Slates.

*The crux of the issue was a proposal to fire the embassy's Soviet employees. Hartman argued that importing American workers to replace the Soviet citizens might increase the embassy's security problems since the new workers would be easy prey for the KGB. He said he urged Shultz to reduce, but not eliminate, the Soviet staff. "I'm confident the recommendations I made were valid," he said last week. "The one thing we didn't count on was Marines committing treason."

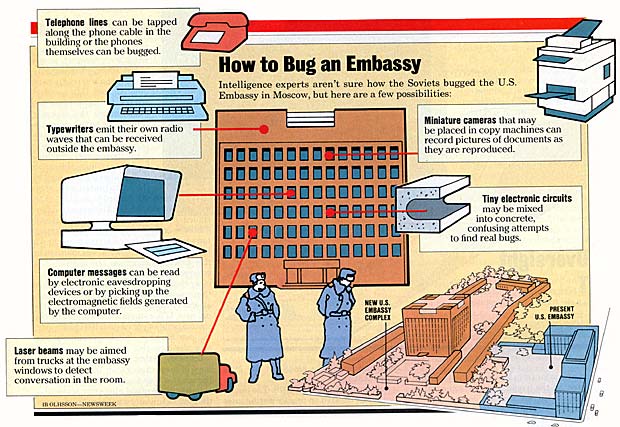

High-Tech Conversation Stoppers

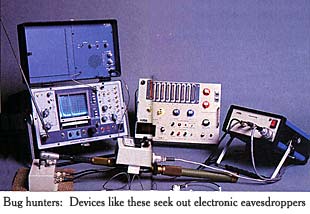

When two visiting U.S. congressmen used kiddie Magic Slates to communicate in the Moscow embassy last week, they were acknowledging one of the open secrets of the surveillance game: bugs have stayed a step ahead of bug detectors. Gobbling up the wares of the microelectronics revolution, the spy's black bag now contains tiny cameras that photograph documents fed into copying machines, lasers that bounce light beams off windows to "read" conversations from the vibrations they cause in the glass and nickel-size bugs that transform the secret electronic emanations of computers into decodable bits and bytes. At the same time, traditional techniques are still effective: the congressmen, who checked on embassy security during their Moscow visit, were equally concerned about high-tech versions of old-fashioned microphones that Soviet agents might have planted in the compound.

The newest listening devices, some as small as fingernails, collect and send signals in ways that confound the debugging brigade. Those that transmit by wires, now thin enough to be woven into carpets and drapes, are exceptionally difficult to ferret out; one would have to X-ray every inch of wall and fabric. Bugs that send data electronically theoretically can be detected by receivers that scan a wide band of frequencies for emitted signals. One popular sweeper, the "nonlinear junction detector," beams out microwaves and detects bugs by the signal they echo back. However, listening devices that transmit not by radio or microwave but by fiber optics, which are hair-thin strands of glass, are "virtually undetectable," says Hall Gershanoff, editor and publisher of the Journal of Electronic Defense. These bugs can convert overheard signals into light pulses that race through the glass fiber to an infrared transmitter embedded in an exterior wall. The transmitter relays the light signals to a listening station. Since no electronic signals are emitted, the system eludes conventional sweeps.

Diplomats in Moscow can try whispering and running water to foil bugs that eavesdrop on conversations, but they cannot so easily counter devices that listen to the chatter of high technology. These bugs pick up the unique electromagnetic signals emitted by each stroke on an electric typewriter or each operation in a computer. Take the typewriter. A bug planted inside can tell which key was hit and send that information to a listening station, where decoders print the words typed at the bugged machine. Like state-of-the-art audio bugs, the latest electronic bugs can also transmit by fiber optics. But even those that rely on conventional transmissions may elude the Americans in Moscow: Charles Taylor, who has taught countersurveillance at Texas A&M University, suspects the Soviets have embedded tiny diodes in the concrete walls of the new American Embassy. These electronic circuits, which resemble flecks of metal, reflect the signals of the security sweeps and so swamp them with false readings.

Bad vibrations: Americans may not even find privacy on the home turf. The Soviets' new Washington embassy, built on a high hill, is perfectly placed to beam laser light from a generator as small as a flashlight toward windows, catching the conversations going on behind them. John Pike of the Federation of American Scientists says that "the White House has put little noisemakers on its windows" to foil the eavesdropping, which can also be hindered by heavy drapes.

What can diplomats do to keep their communications secure? They can trade in their Selectrics for manual typewriters, which don't emit buggable signals. They can banish computer-controlled telephones, which can be programmed remotely to pick up all sounds in the room just like a live microphone. An entire embassy-or key rooms-could be shielded with copper to keep electromagnetic signals from reaching listening posts. But in this day and age, it's virtually impossible to function without computers, and it's immensely difficult and expensive to ferret out sophisticated electronic ears planted in walls. Unless the debuggers make technological breakthroughs of their own, diplomats may have to get used to Magic Slates.

In fact, the U.S. Embassy in Moscow has had security problems for years-and if, as critics now maintain, the 15-year project to build a new embassy compound is an object lesson in mismanagement, the blame can be shared by four successive presidents and their secretaries of state. Despite intermittent U.S. protest, extensive Soviet surveillance has long been an omnipresent fact of life for American diplomats in the Soviet Union: the State Department's counter-strategy generally has been to accept that surveillance as inevitable and reserve its counterespionage defenses for the most sensitive areas of the embassy's operations. The Marines' alleged involvement in Soviet espionage, however, has raised the ante in the Moscow spy wars, since it presumably allowed the KGB to penetrate the inner sanctums of the old chancery building. The bugging of the new chancery building poses much the same threat-continued Soviet eavesdropping on the embassy's CIA team and its code room. "Our assumption was that we could rectify whatever the Soviets had done once we took control of the building," a senior State Department official said. "That may have been too optimistic."

In fact, the U.S. Embassy in Moscow has had security problems for years-and if, as critics now maintain, the 15-year project to build a new embassy compound is an object lesson in mismanagement, the blame can be shared by four successive presidents and their secretaries of state. Despite intermittent U.S. protest, extensive Soviet surveillance has long been an omnipresent fact of life for American diplomats in the Soviet Union: the State Department's counter-strategy generally has been to accept that surveillance as inevitable and reserve its counterespionage defenses for the most sensitive areas of the embassy's operations. The Marines' alleged involvement in Soviet espionage, however, has raised the ante in the Moscow spy wars, since it presumably allowed the KGB to penetrate the inner sanctums of the old chancery building. The bugging of the new chancery building poses much the same threat-continued Soviet eavesdropping on the embassy's CIA team and its code room. "Our assumption was that we could rectify whatever the Soviets had done once we took control of the building," a senior State Department official said. "That may have been too optimistic."